ISTRIAN DEMARCATION

ISTRIAN DEMARCATION

Like this article?

Recommend it to your friends through these services..

Istrian Demarcation, a Croatian Glagolitic monument that describes and regulates the boundaries ("termene and kunfine") between individual Istrian rural municipalities ("komuna"), their feudal lords and the Republic of Venice. It was written as a public legal document in the Croatian language, in Glagolitic script, in the form of a notary instrument. It was first published by Ante Starčević in Latin transcription as Istrian Demarcation from 1325 in the Kukuljević Archive for the Yugoslav chronicle (1852).

The Croatian text dates back to 1325, and the dating was extended by listing the feudal lords who ruled Istria at that time, from Prince Albrecht (who died in1325), Patriarch Raimondo of Aquileia (who died in 1299) and other feudal lords who had their estates in Istria, but who lived at a different time, and could not get together for such a demarcation. This information called into question the formal authenticity of the monument. The very term demarcation is an old Croatian legal term, and was also written in Latin documents in a wide area from Istria to Dalmatia (demarcation facere, 1191, savodiçare, 1237, savodum, 1182), denoting the act of taking possession by walking around the land. Only through demarcation are the boundaries established and the unhindered enjoyment of the property ensured, after the parties have established borders and boundaries on the disputed land.

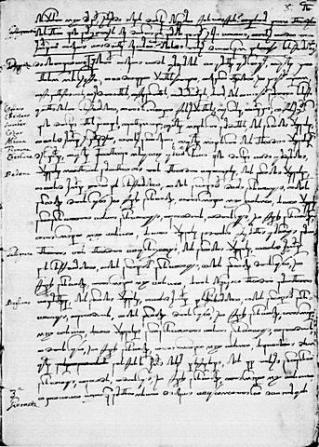

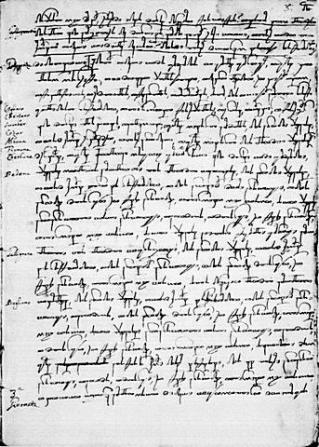

In a period of 21 days, the demarcation commission covered about 150 km of disputed terrain; during that walk, 19 old demarcation documents were presented to the commission confirming ownership, and entered the text of the Istrian Demarcation in an abbreviated form. According to the voice of Croatian monuments, three public notaries accompanied the commission, and each wrote his own original copy, i.e. public document, in Latin, German and Croatian. The notary of the Glagolitic original was the priest Mikula, pastor of Gologorica and chaplain to the prince of Pazin and the lords of the county (i.e. the Istrian petty nobility).

Not a single original has been preserved, although a transcription of the Croatian Glagolitic text has been, which was transcribed in 1502 by priest Jakov Križanić, a notary with imperial and papal authority, who - as stated - transcribed the “instroment” in all three languages, of which only the Croatian Glagolitic has been preserved in a copy transcribed in 1546 by Levac Križanić, a canon from Žminj and Tinjan, who was also a notary. Two of his copies have also been preserved – Kršan’s from 1546 (today in the National and University Library in Zagreb) and Momjan’s (today in the State Archives in Rijeka).

Along with the Momjan transcript, there is also a translation in Italian in the same volume by Ivan Snebal, the Buzet canon and notary by imperial authority from 1548. There are other translations, in both Latin and Italian. Such an unreliable tradition of the Croatian text and its translations, has raised doubts about its authenticity among 19th century Italian historians, and C. de Franceschi published an extensive study on it disputing any value of the monument and considering it a nationalistic product by mid-16th century Croatian Glagolitic priests. Nevertheless, regardless of formal shortcomings and ambiguities, the Istrian Demarcation was used for the purposes for which it was written, i.e. to determine the borders between the Istrian municipalities on the one hand and feudal lords on the other, and that is why it was, in whole or in parts, transcribed as credible testimony.

The scribe and writer of the Istrian Demarcation entered the various demarcation documents from 1275 to 1395 that he had at his disposal into a collection, the "vault", i.e. the entire text. Milko Kos, a Slovenian historian, and expert on the Slovenian and Istrian Middle Ages, was inclined to the opinion of C. de Franceschi, but when he subsequently found the 15th century demarcation documents which follow the Croatian text in its actual content, he changed his opinion about this important monument. B. Stulli also found similar demarcation documents, in German, and thus it was confirmed that Istrian Demarcation was a document that the parties in the dispute believed in, that is, they used it to show their rights. The first publisher of the Italian text, P. Kandler, thought the same, including the document in his Codice Diplomatico Istriano (CDI) collection in the year 1275. He hoped to find a Latin and German original, but did not succeed, although later Ljubić did in fact find a Latin text, but this was also a translation of a Croatian text from 1526, twenty years older than the preserved Croatian text. Istrian Demarcation reflects and contains demarcation documents that were created over a wide time span from the 11th century until the time of a larger demarcation procession, around 1375, when the Habsburgs became owners of the Principality of Pazin.

The writer of the Istrian Demarcation freely used the material that he formulated in a new and original way, without changing the dispositive, that is the boundaries that were described in the previous documents, which meant that he had not created a forgery. The borders described in the monument as disputed remained so after 1375, until the end of the rule of the Venetian Republic in Istria. The author of Istrian Demarcation freely formulates the legal matter and describes conflicts, quarrels and disputes, but also reconciliations, giving words and keeping the "rota" using the author's procedure. He often uses a proverb or saying to emphasize a higher level of legal issues ("Justice cried out for guilt to be chased").

Therefore, Istrian Demarcation is a unique legal historical monument that testifies to the high level of legal life in Istria itself, but also to the early beginnings of literary creativity in medieval Istria. Regardless of the so-called dubious tradition of the text, Istrian Demarcation is an excellent source on how the feudal system was established there, which elements in the rural municipality encumbered it, what was accepted and what was rejected in the implementation of feudal obligations ("services"). Istrian Demarcation reflects the social situation in Istria of the time, which had already become stratified: in addition to foreign feudal lords, secular and ecclesiastical fellows, demarcation was attended by countrymen, insignificant local nobility, knights with golden belts, prefects, "good, trusted people".

During this period, the responsibility towards the feudal lords was on the shoulders of the municipality and county, and not the way it would later become when the burden fell to individuals and families. Istrian Demarcation reflects the economic reality of Istria in medieval times, when ploughed fields were not in dispute while pasture land, ponds and other “land resources” were, because of a very strong expansion in animal husbandry, which added to the insecurity of the countryside. Land was perceived as a source of food and because of that all the natural phenomenon in the countryside was honoured: natural land configuration, ponds, roads, trails and hillsides.

Istrian Demarcation attests to the fact that the position of mayor in Istria in that period was highly respected. It also shows that common law in villages was also well protected by guaranteeing peace and the common benefit of resources used for production - that is, land and water. Istrian Demarcation is also a testimonial of a highly developed written culture in medieval Istria, and the realisation that in diplomatic dealings the Croatian language was on an equal plain with Latin and German (Bratulić, 2009).